Qualitative Research Preparation

This is my final workweek in Ethiopia and I would like to share with you our progress on qualitative data collection for the FLAME study. As many of you know, the FLAME intervention will pair priests with health workers and train them to conduct community outreach to encourage pregnant women to receive safe antenatal and delivery care. Prior to implementing the intervention, we are conducting focus group discussions (with pregnant women, male partners, and priests) and key informant interviews (with health center heads and health extension workers) to gather information that will help us optimize the design of the FLAME intervention. For example, we hope to better understand pregnant women’s healthcare seeking behavior, their preferences for childbirth, and how priests can be involved in community outreach.

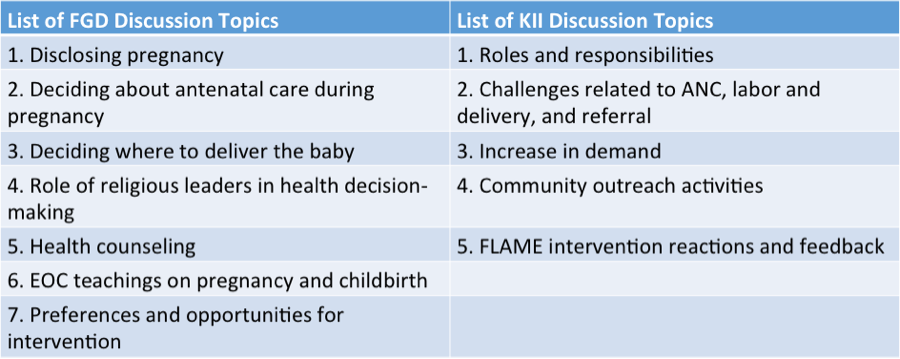

These data will be invaluable in improving the FLAME model to hopefully ensure successful outcomes during intervention implementation. The table below details the primary discussion topics for the focus group discussions and key informant interviews.

Since my arrival in June we have been developing tools and preparing for qualitative data collection. With limited practical experience in qualitative work, it was difficult for me to anticipate the amount of planning and preparation needed. I’m grateful for the opportunity to gain experience in this field and learn firsthand what is required to ensure quality qualitative data collection. To provide a bit context, here are some of the preparation activities we completed throughout my time in Ethiopia:

We developed five discussion guides, one for each of the participant groups – pregnant women, male partners, priests, health center heads, and health extension workers. We applied for ethical approval from the University of Gondar and the University of Washington. We created a participant recruitment plan for each of the five participant groups. We developed standard operating procedures that provide step-by-step instructions for how interviews and focus groups should be conducted. We crafted an analysis plan for how these data will be analyzed to inform the FLAME trial. We recruited qualitative facilitators from the University of Gondar and trained them on our protocol. We developed log sheets to gather demographic information from participants. We negotiated with the University transport office to ensure transportation to rural communities for the interview conduction. And the list goes on…

After many months of preparation (and a few logistical set backs), we are finally in the data collection phase and very eager to learn from our discussions with participants. In the past two weeks we have conducted 2 focus groups with pregnant women, 1 focus group with male partners, 2 interviews with health extension workers, and 1 interview with a health center head. Data collection is moving along nicely and we hope to complete all qualitative research by mid-January.

Qualitative Research Preliminary Findings

Our tools are working – operating procedures, discussion guides, log sheets, etc. – and the discussions have been insightful! I asked Adino, FLAME program manager and qualitative facilitator, about his reactions to his first focus group with pregnant women last week and he said, “I am very pleased with our visit. Although the pregnant women arrived over an hour late, we had a fruitful discussion with them. Our most interesting finding was the influence of mothers and mother-in-laws in pregnant women’s healthcare seeking behavior.” To elaborate, the pregnant women highlighted that mothers are a primary barrier to seeking healthcare during pregnancy and delivery. Mothers will often say ‘I have eight children and delivered all of you at home- you should do the same.’ As a powerful influence in their lives, women struggle to refute their mother’s advice.

Adino also highlighted the challenges women face in disclosing their pregnancy. Women often feel uncomfortable or embarrassed sharing their pregnancy status with the community. Rather than disclosing, they often wait until they are ‘showing’ and community members notice the pregnancy. These feelings of discomfort are exacerbated for unmarried women, who are shunned from the community. Pregnancy out of wedlock is strongly discouraged and the community, including family and friends, often rejects unmarried pregnant women. Sadly, some unmarried pregnant women will attempt suicide or seek abortion to save them from having to disclose their pregnancy status.

I also asked Simegnew, SCOPE fellow and qualitative facilitator, his thoughts on his most recent focus group discussion with male partners. He highlighted a few key findings from the discussion that were particularly interesting. First, he said, “Male partners are very voluntary for their wives to have communication with priests. There is no topic they would not want their wife to discuss with a priest. They believe soul fathers are their ‘fathers’ – they know everything about their lives and women are free to share with them.” This speaks to the integral role priests play in parishioner’s lives and their comfort in discussing personal topics with priests.

Additionally, in regard to delivery, the male partners noted a significant difference between women who live near the health center and village, and women who live in more remote settings. In the village, nearly all women come to the health center for delivery. Conversely, in the remote areas, women often deliver at home because of cultural and distance barriers. Culturally, many rural residents believe that a woman’s first delivery should take place in her mother’s home. Regarding distance, it is challenging for pregnant women to travel numerous kilometers to the health center without access to roads or vehicles; and women do not feel comfortable, or have the resources, to leave behind their children and household responsibilities for multiple days.

Although I will not be in Ethiopia to oversee the remaining focus groups and interviews, I am confident in our qualitative team and eager to hear their results. I am already intrigued by our findings and curious to learn more from the participants. There is no doubt these findings will not only improve implementation of the FLAME intervention, but also provide the SCOPE team with valuable context on maternal healthcare seeking behavior in the North Gondar Zone.